Once, I had a not-so-brief flirtation with Neurosurgery. In medical school, I was awed by the structural and functional specificity of the brain, and fascinated by the almost priestly status of the neurosurgery attendings. Unlike other attendings, they did EVERYTHING themselves – from operating to NICU management (including respirators) to clinics to research. The gung-ho spirit of the specialty is infectious to those it speaks to – which is good because Neurosurgery demands a commitment so overwhelming it is more of a lifestyle choice than a profession.

Unfortunately, my medical school did not have a top-ranked Neurosurgery program, so in my fourth year of medical school, it was up to the Mecca in Boston to steep myself in its culture. I was a curiosity, but the department was professionally committed to my education, which I appreciated. Daily rounds were done with different attendings as I tried to soak up as much as possible so that I could learn how to be a great, academic neurosurgeon.

One night, after a long day of operative procedures and clinics which started at 6am, I was rounding alone with the patriarch of the Neurosurgery department. This man was one of the greats – a society chairman, an expert in an esoteric and challenging area of neurosurgery, a prolific paper and book writer – a man who had dedicated his life to the pursuit of knowledge and surgical skill as a penultimate goal in his 60+ years of life. I was honored that he allowed me to round with him, in truth.

We were seeing the last patient of the day – late at night. It was a woman who had come to him with a brain tumor deemed inoperable by all others. The surgeon had taken her to the OR a few days ago, and tried to wrest the cancer from her brainstem. He proceeded painstakingly, with extreme care. The movements of his hands were precise and slight during the operation. Every time he tried to extirpate the tumor, it caused physiologic instability. It was nerve-wracking to observe. After a number of hours, he closed.

The patient was awake and awaiting the surgeon. She asked him, “Did you get it?” He answered, “No.” She then asked, “Am I going to die?” He answered softly, “Yes.”

The patient started to cry. And then I saw this man, this giant, this scientist and clinician beyond reproach – sit down on the bed and put his arm around the patient. He held her until she stopped crying. It was more than a perfunctory few minutes.

This man, at the pinnacle of his field, could act any way he wanted. He could spin on his heel and leave the room, snap at the patient and tell her to get herself together – and nobody would ever reproach him. Such a gifted surgeon could act any way he wished.

But instead he reached out in a more compassionate way to a suffering patient than many physicians I have known. It was not just programmed, scripted ‘compassion’ learned from a patient experience consultant – he waited there until she had exhausted her grief at that moment. She knew that he was there for her in a human, healing way, now that he could no longer cure her. I stood still, listening to her muffled sobs for at least 15 minutes.

The lesson learned – if the best of the best could show such compassion, so could I. Perhaps other surgeon’s responses I had seen lacking empathy were really a marker of a lesser degree of competence, a cover-up for personal or professional inadequacies instead of a mark of importance.

I ultimately did not choose Neurosurgery as my specialty. But the lesson stayed with me. I hope that in my practice I was able to show this degree of caring to my patients, many of whom came to me in extreme sickness, many of whom I would never be able to cure. I hope that I was able to heal them in some way.

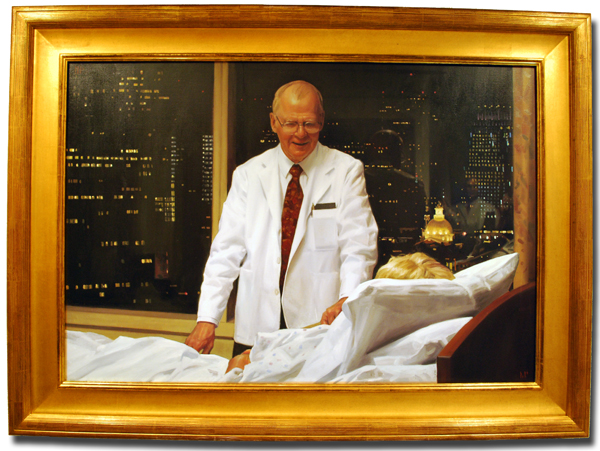

As might be expected with many years passage, he is now gone. But the picture of him is how I remember him, and I will share it with you. (from the MGH dept. of Neurosurgery web site)

Good night, Dr. Ojemann. (1931-2010)

Good night, Dr. Ojemann. (1931-2010)

This is a beautiful post. Thanks for sharing…Dr. Ojemann’s response to his patient not only reflected the compassion that he felt for her, but the impact it had on you did much to ameliorate the “hidden curriculum” in medical school. It is this longstanding schism between teaching medical students to be compassionate caring physicians and then not personally treating patients in a congruent manner that fosters the lack of humanism in medicine. Clearly, Dr. Ojemann understood that although he could not cure his patient, he could heal her.