Lets continue with value as risk. If you missed it, here’s the first post.

Lets continue with value as risk. If you missed it, here’s the first post.

Providers assert that insurers hold most if not all the cards, collecting premiums and denying payment while holding large datasets of care patterns. I’ve heard, “if only we had access to that data, we could compete on a level playing field.”

I am neither an apologist for nor an insider in the insurance industry, but is this a “grass is always greener” problem? True, the insurer has detailed risk analysis on the patient & provider. Yes, the insurer does get to see what all providers are charging and coding in their coverage. And the insurer can deny or delay payment knowing that a certain percentage of these claims will not be re-submitted.

But the insurer also has deep institutional knowledge in risk-rating their clients. Consider the history of health insurance in the US. Advancing medical knowledge advanced treatment cost. When medical cost inflation exceeded CPI insurers modeled and predicted estimated spend with hard data. If individuals had medical conditions which would cost more ultimately than premiums received they failed medical underwriting. The insurers are private, for-profit businesses, and will not operate at a loss willingly.

To optimize profitability, insurers collected data from not only the insurance application, but also claims data, demographic data from consumer data brokers, financial data, information from other insurers (auto, home, life), and probably now Internet data (Facebook, etc…) to risk-rate the insured. Were they engaged in a risky lifestyle? Searching the net for serious genetic diseases?

Interestingly, the ACA changed this to only permit 1) Age 2) Smoking 3) Geographic location as pricing factors in the marketplace products. The marketplace products have been controversial, with buyers complaining of networks so narrow to be unusable , and insurers complaining of a lack of profitability, which has caused them to leave the market. Because the marketplace pools must take all comers, and many who entered the pools had not had insurance, there is some skew towards high-cost, sicker patients.

Consider a fictional medium-sized regional health insurer in three southern states specializing in group (employer) insurance – Southern Health. They are testing an ACA marketplace product. The geographic area they serve has a few academic medical centers, many community hospitals competing with each other, and only a few rural hospitals. In the past, they could play the providers off one another and negotiate aggressively, even sometimes paying lower rates than Medicare.

However, one provider – a fictional two-hospital system – Sun Memorial – hired a savvy CEO who developed profitable cardiac and oncology service lines leveraging reputation. Over the last 5 years, the two-hospital group has merged & acquired hospitals forming a 7-hospital system, with 4 more mergers in late-stage negotiations. The hospital system changed its physicians to an employed model and then at next contract renewal demanded above Medicare rates. As such, Southern Health did not renew their contract with Sun Memorial. In the past, such maneuvers ended conflict quickly as the hospital suffered cash flow losses. However, now with fewer local alternatives to Sun Memorial; patients were furiously complaining to both Southern Health and their employer’s HR department that their insurance would not cover their bills. Pushback on the insurer by the local businesses purchasing benefits through Southern Health happened as they now threatened not to renew! The contract was eventually resolved at Medicare rates, with retroactive coverage.

The marketplace product is most purchased by the rural poor, operating on balance neutral to a slight loss. As the Southern Health’s CEO, you have received word that the your largest customer, a university, has approached Sun Memorial about creating a capitated product – cutting you out entirely. The CEO of Sun Memorial has also contacted you about starting an ACO together.

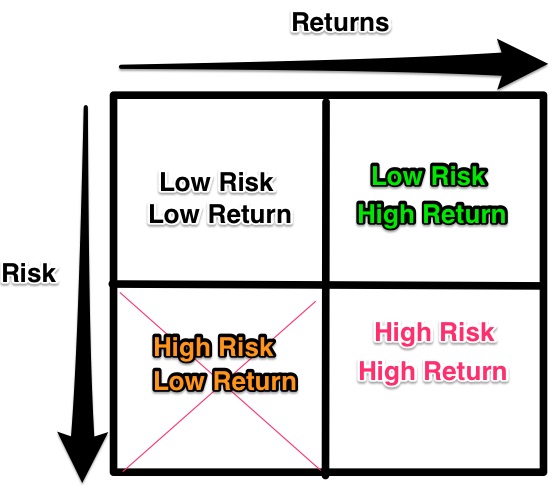

Recall the risk matrix:

Low Risk/Low return: who cares?

High Risk/Low return: cancelling provider contracts as a negotiating ploy.

High Risk/High return: Entering into an ACO with Sun Memorial. Doing so shares your data with them & teaches them how to do analytics. This may negatively impact future negotiations and might even help them to structure the capitated contract correctly.

Low Risk/High Return: Pursue lobbying and legal action at the state/federal level to prevent further expansion of Sun Memorial. Maintain existing group business. Withdraw from unprofitable ACA marketplace business.

As CEO of Southern Health, you ultimately decide to hinder the chain’s acquisition strategy. You also withdraw from the marketplace but may reintroduce it later. Finally, you do decide to start an ACO – but with the primary competitor of Sun Memorial. You will give them analytic support as they are weak in analytics, thereby maintaining your competitive advantage.

From the insurer’s perspective the low risk and high return move is to continue the business as usual (late stage, mature company) and maintain margins in perpetuity. Adding new products is a high-risk high reward ‘blue ocean’ strategy that can lead to a new business line and either profit augmentation or revitalization of the business. However, in this instance the unprofitable marketplace product should be discontinued.

For the insurer, value is achieved by understanding, controlling, and minimizing risk.

Next, we’ll discuss things from the hospital system’s CEO perspective.