I came across this wonderful piece by Bruce Davis MD on Physician’s Weekly.com about “The Etiquette of Help”. How do you help a colleague emergently in a surgical procedure where things go wrong? As proceduralists, we are always cognizant that this is a possibility.

“Any Surgeon to OR 6 STAT. Any Surgeon to OR 6 STAT.

No surgeon wants to hear or respond to a call like that. It means someone is in deep kimchee and needs help right away.”

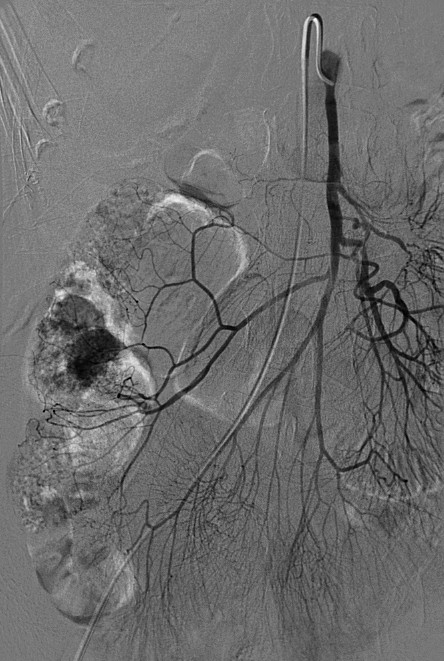

I was called about an acute lower GI bleed with a strongly positive bleeding scan. I practice in a resort area, and an extended family had come here with their patriarch, a man in his late 50’s. (Identifying details changed/withheld – image above is NOT from this case). He had been feeling woozy in the hot sun, went to the men’s room, evacuated a substantial amount of blood, and collapsed.

As an interventional radiologist, I was asked to perform an angiogram and embolize the bleeder if possible. The patient was brought to the cath lab; I gained access to the right femoral artery, and then consecutively selected the celiac, superior mesenteric, and inferior mesenteric arteries to evaluate abdominal blood supply. The briskly bleeding vessel was identifiable in the right colonic distribution as an end branch off the ileocolic artery. I guided my catheter, and then threaded a smaller micro-catheter through it, towards the vessel that was bleeding.

When you embolize a vessel, you are cutting off blood flow. Close off too large a region, and the bowel will die. Also, collateral vessels in the colon will resupply the bleeding vessel, so you have to be precise.

Advancing a microcatheter under fluoroscopy to an end vessel is slow, painstaking work requiring multiple wire exchanges and contrast injections. After one injection, I asked my assisting scrub tech to hand me back the wire.

“Sir, I’m sorry. I dropped the wire on the floor.”

“That’s OK. Just open up another one.”

“Sir, I’m sorry. That was the last one in the hospital.”

“There’s an art to coming in to help a colleague in trouble. Most of us have been in that situation, both giving and receiving help. A scheduled case that goes bad is different from a trauma. In trauma, you expect the worst. Your thinking and expectations are already looking for trouble. In a routine case, trouble is an unwelcome surprise, and even an experienced surgeon may have difficulty shifting from routine to crisis mode.”

We inquired how quickly we could get another wire. It would take hours, if we were lucky. The patient was still actively bleeding and requiring increasing fluid and blood support to maintain pressure. After a few creative attempts at solving this problem, it was clear that it was not going to be solved by me, today, in that room. It was time to pull the trigger and make the call the interventionalist dreads – the call to the surgeon.

The general surgeon came down to the angio suite and I explained what was happening. I marked the bowel with a dye to assist him in surgery, and sent the patient with him to the OR. The patient was operated on within 30 minutes from leaving my cath lab, and OR time was perhaps 45 minutes. After the procedure was done the surgeon remarked to me that it was one of the easiest resections ever, as he knew exactly where to go from my work. The surgeon never said anything negative to me, and we had a very good working relationship thereafter.

“The first thing to remember when stepping into a bad situation is that you are the cavalry. You didn’t create the situation, and recriminations and blame have no place in the room. You need to be the calm center to a storm that started before you got involved. Sometimes that’s all that is needed. A fresh perspective, a few focused questions, and the operating surgeon can calm down and get back on track.”

I saw the patient the next day, sitting up with a large smile on his face. He explained to me how happy he was that he had come here for vacation, that it was the trip of a lifetime for him, and that he was looking forward to attending his youngest daughter’s wedding later that year. He told me he lived in a rural Midwest area, hours from a very small hospital without an interventionalist, and if this had happened at home, well, who knows?

If I had not objectively assessed my inability to finish the case because of equipment issues, well, who knows?

If I had been prideful and unwilling to accept my limitations at that time, well, who knows?

If I had been more concerned with my reputation or what my partners would think, well, who knows?

I sincerely hope that my patient has enjoyed many years of happiness with his family in his bucolic rural Midwestern home. I will never see him again, but I do think of him from time to time.